Before digital targeting and data mining defined modern politics, campaigns were built on hard ground, human instinct, and the party machine.

Watch First: Mark Block on Campaign Now Podcast

What to Know:

- Block became the first 18-year-old elected to office in Wisconsin after the voting age was lowered

- He began organizing for Nixon in 1972, where campaign cash was handed out without regulation

- In early campaigns, outreach relied heavily on radio, posters, letters to the editor, and in-person events

- The Republican Party was decimated after Watergate and had to be rebuilt from the ground up

- Block was among the first in Wisconsin to experiment with data-driven campaigning using Super Calc in 1979

In an age before campaign algorithms and social media virality, political strategy in America was grounded in personality, party infrastructure, and paper files. Few people experienced that transformation more directly than Mark Block, whose career began in the grassroots of 1970s Wisconsin and later exploded onto the national stage with Herman Cain’s presidential campaign. His story offers an unvarnished look at what campaigning looked like in the pre-digital era—and what we've lost since.

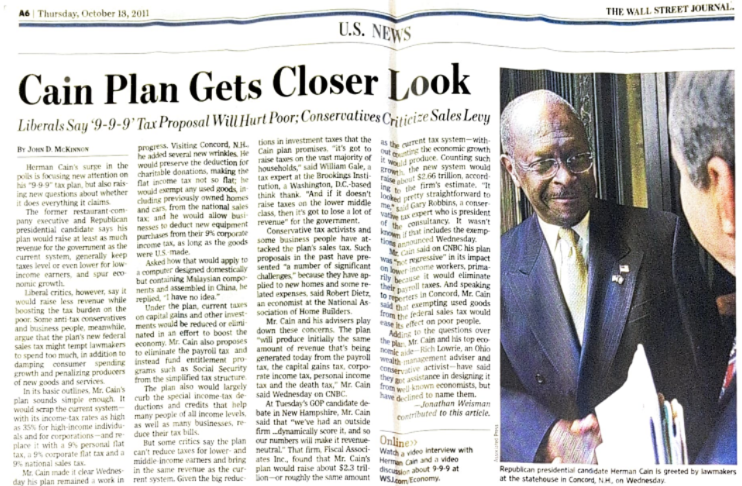

The Wall Street Journal 2011 photo of newspaper clipping

🎧 Catch the full conversation with Mark Block on YouTube or SoundCloud to hear his candid take on old-school politics, media chaos, and what still works today.

Early Roots: Small-Town Politics and a Teenage Power Streak

Block’s political origin traces back to small-town Wisconsin. In the small town of Waiwiga, with a population of 682, he demonstrated early leadership, securing consecutive elections as freshman, sophomore, junior, and senior class president, ultimately culminating in his role as student council president.

“That’s kind of what compelled me then to get involved in a political arena.”

In 1972, he became Nixon’s campus chair at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh and an alternate delegate to the Republican National Convention. His first taste of national campaign work came not through a strategy memo, but through a briefcase full of money.

“Roger Stone had a suitcase full of cash... before Watergate, before Federal Election Commission laws and regulations. And he opened his briefcase in his full 100-dollar bills, and he started grabbing them and handing them to me, and said, ‘You gotta do a beer party for Nixon, you gotta do this for Nixon.’”

One year later, Block became the first 18-year-old ever elected to public office in Wisconsin, after the 26th Amendment lowered the voting age.

“I probably won because some of my campaign workers handed out joints in the dorm room.”

He won that election by 29 votes. His first day on the Winnebago County Board made it clear that this wasn’t a college experiment anymore.

“There was probably an average age of 70 in that room. I had hair down to my shoulders. And here I come in with long hair, no experience, and a welfare reform bill. The unions hated it. That’s when I understood the power of unions. They came down at me like a ton of bricks.”

That was Block’s introduction to hardball politics. And it came at a time when the Republican Party itself was in disarray. Watergate had detonated whatever national infrastructure was left after Nixon’s resignation.

“The Republican Party is gone, done, finished, right? So I had to rebuild from literally nothing, and that’s what they did. They had people go out and recruit young people to run for local offices.”

Block was one of them. He soon became a legislative assistant in Washington, D.C., working on agricultural policy. The disconnect between political staff and the industries they oversaw left a lasting impression.

“I could have put a picture of a Guernsey cow and a whitetail deer in front of these people, and they couldn't have told me which one was which.”

The Party Was the Machine

In the 1970s and early 1980s, political campaigns didn’t just rely on parties—they were defined by them. Before PACs, SuperPACs, and independent expenditure groups fractured the ecosystem, the party was the skeleton and muscle of every serious campaign. From messaging to manpower, the party’s infrastructure controlled how candidates emerged, who got funded, and what boots hit the ground.

“The parties back then—you needed them,” Block said. “Today, quite frankly, I think they’re more of a hindrance than a help.”

That sentiment reflects a seismic shift. In the post-Watergate fallout, the Republican Party was on life support. “The Republican Party is gone, done, finished,” Block recalled. “So I had to rebuild from literally nothing.” That rebuilding process wasn’t theoretical—it meant recruiting young candidates to run for school board, city council, and county commission just to keep a bench alive.

Block was one of them, pulled in by party veterans like Congressman Bill Steiger, and he quickly rose through the ranks. There was also an unspoken hierarchy. Party bosses, such as John MacIver, a mentor to Block, held the keys to career advancement. “

At the time, if you didn’t have MacIver’s blessing, you weren’t going anywhere,” Block explained. “It was real politics. Party politics.”

What’s striking is how decentralized campaigns have become today. Back then, a congressional endorsement came from your local Republican caucus—not your follower count. And losing the caucus could mean losing everything, as Block saw firsthand during a 1978 campaign that ended in chaos (and a Milwaukee Journal headline).

How Campaigns Began to Evolve

Back home, campaign tactics in the 1970s and early 1980s were raw and direct. There were no voter databases, no digital outreach tools.

“It was just your basic, you know, knocking on doors, introducing yourself, some yard signs, and TV commercials. Probably mass meter radio was bigger than TV.”

Radio was everything. It reached voters during their workday, in their cars, and at home.

“They get a lot of money on radio, cause I think more people got their information from radio, quite frankly.”

When President Gerald Ford visited Oshkosh in 1976, the entire city was plastered with hand-drawn posters, not digital alerts.

“You would have had dozens of people putting up posters all over town, interesting to get the word about the event. You don't see that. That’s crazy.”

Media coverage wasn’t manufactured. It was earned—literally.

“Letters to the editor, that was your media.”

One turning point in Block’s own evolution came through technology. While working at NCR selling early personal computers, he encountered spreadsheet software called Super Calc. In 1979, while volunteering for George H.W. Bush, he used it to input voter files and shared it with Wisconsin political heavyweight John MacIver.

“He was flabbergasted. In one second, you could change all these numbers, and if you get two more percentage points here, this is what happens.”

That early foray into data shifted how he saw campaigns.

“It’s the first time somebody of his statue, I think, really started grasping what's eventually changed—how you run a political campaign. A data-driven campaign, basically.”

The Dawn of Direct Mail—and Karl Rove’s Rise

If digital ads and geo-fencing are the blood of today’s campaigns, then direct mail was the lifeblood of campaigns entering the 1980s. But in the early-to-mid ’70s? It barely existed.

“There was really not even direct mail back then,” Block said. “That really came out when [Karl] Rove started his company in Texas.”

That was the inflection point—around 1984 to 1988—when consultants began building entire firms around voter targeting by mail. And Rove wasn’t just one of them. He was the one. His Texas-based operation pioneered the model: personalized letters, targeted appeals, precinct-level messaging. It helped usher in a new kind of campaign apparatus—one that could bypass party infrastructure altogether.

“I remember meeting with Karl Rove to talk about doing direct mail for Tommy Thompson in 1990,” Block recalled. “We went with someone else, and that’s probably why Rove bashed me during the Cain campaign. He didn’t like me.”

That anecdote is more than just personal. It’s emblematic of a turning point: when campaigns became more consultant-driven, more data-aware, and more professionalized. The rise of direct mail was the beginning of a transformation that now spans predictive algorithms, microtargeting, and A/B tested TikToks.

The Wall Street Journal

Before all that, campaigns relied on posters, radio ads, and grassroots buzz. The idea that you could raise millions through the mail? Revolutionary.

And Rove’s success helped seed what would become the modern GOP fundraising juggernaut.

By 1990, during Tommy Thompson’s gubernatorial run, Block and MacIver built one of the most coordinated influencer campaigns of the pre-Internet age. They recruited sheriffs, county board members, mayors, and state officials to back Thompson.

“All of those elected officials are winners, right? They’re elected, people elected them, they're winners—and have them speak for you. They became influencers before influence. They were the influencers of that time.”

That year, Thompson won Milwaukee County for the first time in nearly half a century.

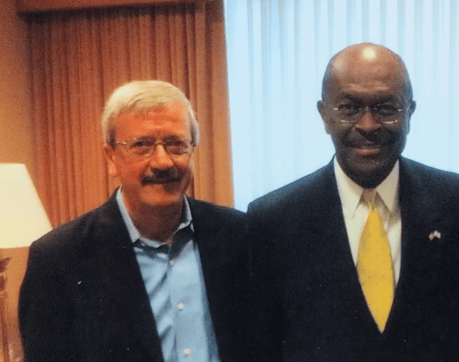

Mark Block (left) and Herman Cain (right)

Mark Block’s reflections reveal more than nostalgia. They map out a campaign world before polling microtargets and Facebook algorithms. It was a system rooted in trust, effort, and structure—where parties mattered, relationships were currency, and spreadsheets were cutting-edge. And while today’s campaigns look almost nothing like those of the 1970s, some lessons remain timeless.

“You always needed to think outside the box,” Block said. “That hasn’t changed.”

Wrap Up

Mark Block’s firsthand account of campaigning in the 1970s and 1980s strips modern politics of its digital polish and brings us back to the tactile, unpredictable nature of early American electioneering. At its core, this was a system driven not by metrics but by momentum. Block’s early use of Super Calc hinted at the data revolution to come, but his true education came from dorm room debates, town hall showdowns, and face-to-face persuasion. It was a time when organizing meant walking blocks, not buying ads. When political power meant knowing who to call, not just what to post.

Block’s early career shows campaigning’s constant principles: trust, hustle, adaptability, despite evolving tools. His lessons offer not just a glimpse into the past, but a blueprint for grounding today’s political strategies in something more human, more tactile, and ultimately more lasting.

🎙️ Learn more about Mark Block’s early years and campaign insights by tuning into The Conversation with Mark Block podcast series on YouTube and SoundCloud.