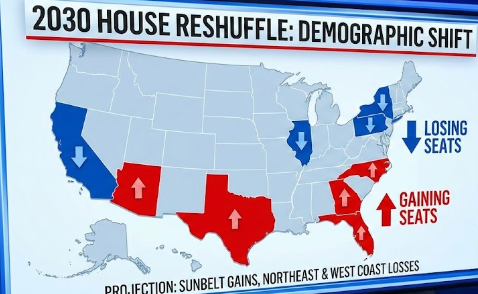

A demographic shift from the Northeast and West Coast to the Sunbelt is projected to alter the balance of power in Washington.

What to Know

- New 2030 census projections show traditionally blue states like California and New York are expected to lose six or more congressional seats combined.

- Fast-growing red and red-leaning states, particularly Texas and Florida, are projected to gain a significant number of House seats.

- The shift is driven primarily by domestic migration as Americans move in search of jobs, affordable housing, and lower taxes rather than partisan manipulation.

- Reapportionment will directly affect the Electoral College, reshaping the presidential map beginning in 2032.

- These changes will set the stage for intense redistricting battles after 2030 as both parties fight to lock in structural advantages for the next decade.

New population projections tied to the 2030 census point to a slow but powerful political realignment already underway in the United States. Congressional representation is poised to move away from long-dominant blue states and toward faster-growing red and Sunbelt states. This shift is not the result of clever map drawing or election-cycle tactics. It is the downstream effect of where Americans are choosing to live, work, and raise families.

The consequences of this realignment will stretch far beyond a single election. House control, presidential strategy, and national party coalitions throughout the 2030s will all be shaped by decisions millions of Americans are making now about cost of living, economic opportunity, and quality of life.

The Numbers Point South

Across multiple independent analyses, the takeaway is increasingly hard to ignore. States that have anchored Democratic power for decades are losing population share, and with it, congressional clout. California, New York, and Illinois are all projected to lose House seats after the 2030 reapportionment. Reporting by Fox News highlights estimates showing those states shedding as many as six seats collectively, with some broader models pushing the combined loss even higher.

Meanwhile, growth is consolidating in the South and parts of the Mountain West. Texas and Florida stand to be the biggest winners, with projections frequently showing them gaining eight or more seats combined. Arizona, Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee are also positioned to expand their House delegations as population inflows continue.

This is not a one-cycle anomaly. Census data across multiple decades shows a sustained migration away from high-cost coastal metros toward lower-cost regions with expanding labor markets and housing supply. The 2030 reapportionment is not creating this shift. It is simply the moment when long-running demographic trends harden into unavoidable political math.

Why Migration Is Driving the Shift

As reported by Associated Press, immigration and enforcement politics are colliding with a broader, quieter force reshaping the electoral map: domestic migration. Americans are moving within the country at higher rates than in prior decades, and those moves are not random. They are directional, sustained, and increasingly political in their consequences.

The push factors are well established. High housing costs, layered taxation, congestion, and regulatory friction continue to push residents out of legacy coastal states. The pull factors are just as clear. Sunbelt and interior states offer cheaper housing, expanding job markets, warmer climates, and, in many cases, lighter tax and regulatory burdens.

"‘Really red states are going to be purple states really soon if the Republican party doesn't work to win over Hispanics and Asians.’"

This quote is from Jeremy Robbins, the executive director of the Partnership for a New American Economy, and it directly speaks to the political shifts happening in traditionally conservative states. This migration wave cuts across party lines and demographics. Retirees, young families, remote workers, and middle-income households priced out of major metros are all part of the flow. That diversity complicates any clean partisan narrative. Population gains do not automatically translate into durable political control.

Crucially, many of the fastest-growing areas inside red states are urban and suburban corridors that have been trending more Democratic over time. Growth around Dallas, Austin, Atlanta, Phoenix, and Tampa is reshaping internal state politics even as those states gain seats nationally. The result is a paradox: red states gain power on paper, while their internal political balance becomes more volatile and less predictable.

Blue State Losses Are Becoming Quantifiable

Census trend analyses reported by the New York Post project that New York and California will lose a combined six House seats after the 2030 census, roughly a 10% reduction in congressional representation for each state. New York is expected to lose two seats, California four, continuing a decades-long decline tied to population stagnation. Both states remain down roughly 200,000 residents since the pandemic, with New York adding just 1,000 residents between mid-2024 and mid-2025.

The contrast with the Sun Belt is stark. Texas has added about 400,000 residents and Florida roughly 200,000, growth translating into an estimated four new House seats each. That represents a 10% boost in representation for Texas and a 14% increase for Florida. Cost pressures help explain the divergence: New York residents pay about $5,000 more per capita in taxes than the national average and roughly $7,000 more than residents of Texas or Florida, while average New York City rents climbed to $5,686 per month by late 2025.

Electoral College Consequences

New census projections reported by The Center Square, drawing on U.S. Census Bureau data, underscore how reapportionment after 2030 will directly reshape the Electoral College. Because each state’s electoral votes are tied to its House seats, population shifts translate immediately into presidential math. Current estimates show Texas gaining up to four seats, Florida gaining two to four, and additional gains spread across North Carolina, Georgia, Arizona, Utah, and Idaho, while California could lose four seats and states like New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Oregon each lose one.

Those changes expand the Republican baseline before campaigns even begin. Additional electoral votes in Texas and Florida alone would move the GOP several steps closer to 270, reducing the need to flip traditional battlegrounds. At the same time, Democratic losses in large blue states compress their Electoral College cushion, increasing reliance on a narrower set of swing states and forcing more aggressive competition in faster-growing Southern and Mountain West regions.

This does not guarantee a permanent advantage for either party, but it does raise the cost of standing still. As redistricting analysts have noted, coalitions that delivered victories in the 2010s and early 2020s may no longer be sufficient in a map where population gravity continues to tilt southward. After 2030, winning the presidency will depend less on defending legacy strongholds and more on adapting to where voters actually live.

Redistricting Wars Ahead

Reapportionment is only the opening act. As The Cook Political Report documents in its 2025–26 mid-decade redistricting tracker, the real fight begins once new seats force states back to the map-drawing table. Texas, Florida, North Carolina, Georgia, and California are already flagged as high-risk arenas, where legislatures, courts, and commissions are poised to clash over lines that could shape control of the House for the next decade.

Screenshot of interactive map by Cook Political

Constraints on aggressive map-drawing are real, but uneven. Independent commissions in states like California limit partisan overreach, while legislatures in Texas and North Carolina continue to test the outer bounds of what courts will tolerate. Cook Political Report analysts note that public backlash, litigation risk, and internal party fractures increasingly act as guardrails, especially in fast-growing metro regions where voter coalitions are less predictable than in past cycles.

What has changed most is the strategic math. As Cook’s analysis makes clear, population growth no longer guarantees partisan gain. Migration is producing electorates that are more mobile, more diverse, and more volatile than the maps of the 2010s were designed to handle. Post-2030 redistricting will not be a simple exercise in locking down advantage. It will be a high-stakes negotiation between demographic reality, legal limits, and political risk.

Wrap Up

The population trends shaping the 2030 census are already well underway, and their political consequences are unavoidable. Representation is moving south. Power is following people. For Democrats, the challenge will be defending relevance in shrinking strongholds while expanding competitiveness in growing regions. For Republicans, the opportunity comes with the responsibility of holding together a coalition that is becoming more diverse and more urban with each census cycle.

This reshuffle will not decide elections on its own. Candidates, issues, and economic conditions will still matter. But the structural terrain of American politics is changing, and it is changing in ways that will define House control, presidential strategy, and party coalitions for the next decade.