As both parties race to redraw lines and game out the road to 270, the next two cycles are shaping up to be as much about structure, law, and process as persuasion.

What to Know

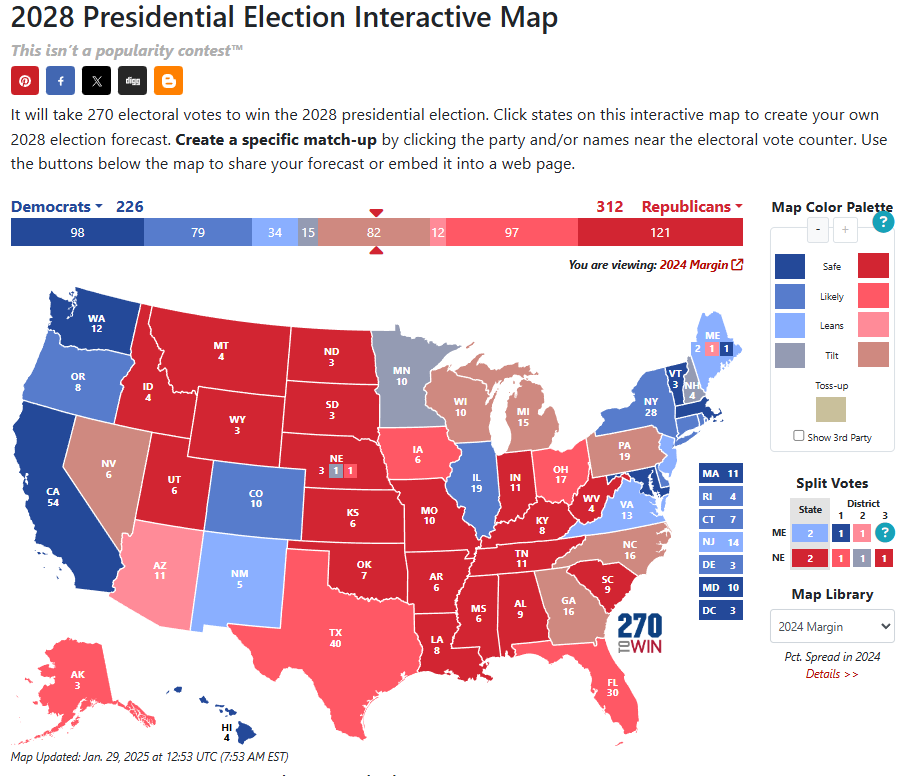

- It will still take 270 electoral votes to win the presidency in 2028, and early interactive maps are already influencing donor behavior, media narratives, and campaign strategy.

- A wave of mid-decade redistricting is underway, with Republicans and Democrats openly responding to each other’s moves across multiple states.

- Democrats need to gain just three seats in the 2026 midterms to flip control of the U.S. House, making even marginal district changes highly consequential.

- North Carolina’s legislature has reshaped its only current swing district, targeting a Democrat who won by less than two points.

- Alongside map fights, campaigns are increasingly planning for post-election conflict, including recounts, lawsuits, and efforts to challenge vote counting itself.

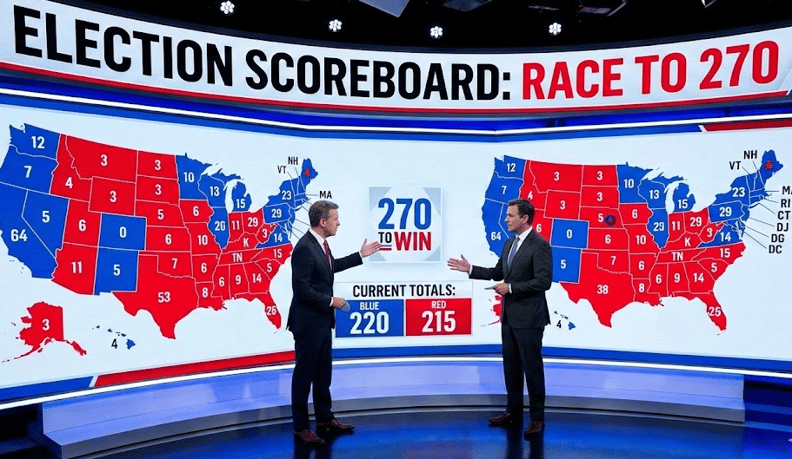

American elections have always been governed by math, but the modern political environment has stripped away much of the pretense. Today, elections are openly discussed as scoreboards. Interactive maps reduce the presidency to a numerical threshold, with every state assigned a fixed value and every coalition judged by whether it reaches 270. This framing is not just for hobbyists or pundits. It is shaping how campaigns allocate money, recruit candidates, and decide where to fight and where to retreat.

At the same time, the institutional guardrails that once limited how often and how aggressively maps could be redrawn are under pressure. Mid-decade redistricting, once rare and controversial, is becoming normalized. Legislatures are treating district lines as adjustable instruments rather than settled facts.

The result is a political landscape where the fight is not only over voters, but over the terrain itself and, increasingly, over how close elections are administered after Election Day.

The Road to 270 Is Now a Strategic Constraint

The widespread use of interactive Electoral College maps, particularly tools like 270toWin and the JJ Election Map, has quietly reshaped how presidential campaigns think and behave. When the entire race can be reduced to a live, clickable tally of electoral votes, strategy becomes arithmetic first and persuasion second.

Coalitions are no longer evaluated by energy, growth potential, or long-term realignment. They are judged by whether they reach 270 on a screen. The map leaves little room for rhetorical flexibility. If the numbers do not add up, the argument is over.

Screenshot of interactive map from 270toWin

This dynamic has produced several concrete effects on campaign decision-making. Strategic imagination narrows as campaigns focus on defending existing paths rather than testing new ones.

States get mentally sorted into fixed columns early, often years before voting begins, making it harder to justify investment even when demographic or political conditions are shifting beneath the surface. Donor behavior follows the same logic. Money flows toward scenarios that look viable on the map today, not toward persuasion efforts that might pay off over multiple cycles but complicate the immediate math.

The map mindset also shapes media coverage and elite perception. Interactive forecasts encourage headlines that frame elections as settled or inevitable based on projected combinations, even when those projections rest on thin assumptions. That framing feeds back into campaign strategy, reinforcing risk aversion and discouraging outreach beyond the most familiar battlegrounds.

Over time, perception hardens into strategy, and strategy hardens into reality. The road to 270 has not just become the goal. It has become a constraint that limits how campaigns think about growth, coalition change, and political possibility.

Mid-Decade Redistricting as an Escalating Arms Race

Mid-decade redistricting has moved from rare exception to open tactic, and Congress’s own research arm has made clear why the escalation is legally possible. According to Congressional Research Service in its August 2025 brief Mid-Decade Congressional Redistricting: Key Issues (IF13082), nothing in the U.S. Constitution or federal statute prohibits states from redrawing congressional maps between censuses. Once that reality is accepted, restraint becomes a political choice rather than a legal requirement.

Texas’s 2025 move to redraw its map mid-decade marked the clearest modern trigger. Other states quickly signaled they were exploring similar options, including California, Missouri, and North Carolina.

What separates this moment from past redistricting fights is the lack of pretense. Lawmakers are no longer framing these efforts as technical fixes or population adjustments. They are openly responding to partisan moves elsewhere, treating map changes as countermeasures in a zero-sum contest for seats. CRS notes that while mid-decade redistricting was common in the 19th century, it largely faded in the modern era until recent cycles reopened the door.

The legal backdrop encourages escalation. The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that partisan gerrymandering claims present no manageable federal standard, most notably in League of United Latin American Citizens v. Perry. As CRS outlines, enforcement is left to state constitutions, state courts, and ballot initiatives, which vary widely. That uneven terrain creates incentives for aggressive actors to move first, knowing retaliation is likely but enforcement is uncertain.

North Carolina: A Single District With National Consequences

North Carolina offers a clean example of how this logic plays out. Republicans already control ten of the state’s fourteen House seats. There is only one district that can plausibly swing. That district is held by Democrat Don Davis, who won his last race by less than two percentage points.

Representative Don Davis

The newly approved map reshapes that district by adding Republican-leaning coastal voters and shifting other precincts into adjacent districts. The governor cannot veto the change, and legal challenges are expected. But from a purely strategic perspective, the move makes sense. Turning a single competitive seat into a safer one could be the difference between holding or losing the House.

Why 2026 Is the Inflection Point

The 2026 midterms represent a shift from traditional campaign assumptions to a far more controlled and contingency-driven approach to elections. While midterms have historically favored the party out of the White House, campaigns are no longer willing to rely on historical patterns alone. The current environment rewards parties that reduce uncertainty well before voters cast ballots. Mid-decade redistricting is one tool for doing that, but it is not the only one. Candidate recruitment is increasingly tailored to newly drawn or anticipated district lines, and legal infrastructure is being built early to defend maps, challenge opponents, and respond quickly to adverse rulings. These decisions are shaping budgets, staffing, and strategy years in advance, not months.

Campaigns are now operating under multiple parallel scenarios. A district may flip on paper but remain competitive in practice. Courts may intervene late in the cycle, forcing rapid adjustments. Margins may be narrow enough to trigger recounts or legal challenges that stretch well beyond election night. These are no longer hypothetical risks discussed in strategy memos. They are operational realities that influence how campaigns allocate resources, where they invest early money, and how aggressively they prepare for conflict.

Wrap Up

Heading into 2026, campaign strategy is being reshaped by structure more than sentiment. Persuasion still matters, but it is no longer sufficient on its own. Votes must be won, counted, and defended in an environment where maps can change midstream, margins are razor thin, and post-election procedures are increasingly contested. Redistricting is now a live variable, not a background condition, and campaigns that fail to integrate map intelligence early risk building strategies on terrain that no longer exists.

At the same time, election administration has become a core strategic concern. How ballots are processed, how provisional votes are handled, and how results are certified can influence outcomes as much as late-cycle messaging. Campaigns are being forced to internalize the math of the map without allowing it to narrow their vision or write off emerging battlegrounds too soon. The lesson is blunt. Winning the argument is not enough. The campaigns that succeed in 2026 will be those that understand the map, the law, and the mechanics of the process as thoroughly as they understand voters, and prepare for the conflict that now follows close elections as a matter of course.