Every few years a book comes along that quietly explains far more about our politics than the daily news ever will. Katherine Cramer’s The Politics of Resentment is one of those books. On its face, it is an ethnographic study of Wisconsin in the years leading up to Scott Walker. I first read this book in December 2025, after it was mentioned on a podcast about how Democrats have lost the rural vote. As someone who grew up in rural northern Wisconsin — in Forest County — that experience has shaped my worldview, and I strongly resonate with what Katherine’s subjects are saying. I stand in solidarity with rural Americans. Over seventeen years in politics in Wisconsin and across the country, I’ve learned that their comments about politicians and far-away cities controlling the political system are spot on and have been confirmed by the political creatures I encounter. I treat this book as a field manual for understanding the forces that will shape 2026 and future elections — and the space where weak political parties are being replaced by focused third-party groups.

.jpg?width=235&height=353&name=book%20cover%20(1).jpg)

Katherine’s basic move is simple but rare: she goes out into small towns, sits down at regular coffee groups and lunch tables, and mostly listens. Out of those conversations she develops the idea of “rural consciousness,” a way people in small places understand who has power, who is ignored, and who is getting more than they deserve.

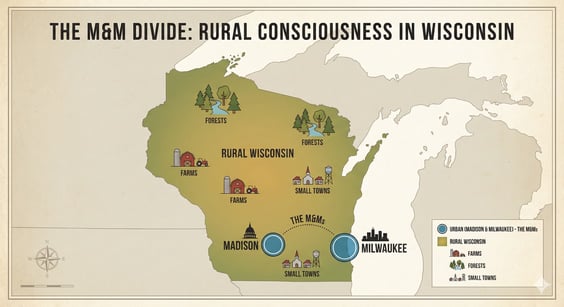

Rural consciousness, as she describes it, rests on three perceptions. First, that decision-makers in Madison, Milwaukee, and Washington overlook rural communities. In one memorable phrase, people divide the state into “the M&Ms”—Madison and Milwaukee—and everybody else. Second, that rural taxpayers do not get their fair share back; money flows out to government and comes back as programs and attention for someone else. Third, that rural values and ways of life are misunderstood or actively disrespected by urban professionals and public employees.

Katherine is at her strongest when she lets those voices speak. A man jokes that you could buy a horse and keep it in Madison because that’s where “they keep all the bullshit.” A woman in a lunch group says her town is “hung out there to dry.” A group that knows exactly how they are seen from the cities half-ironically calls itself a “redneck coffee klatch.” None of these lines are about a specific bill. They are about status and respect.

One of the most important threads in the book is resentment toward the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Over and over, Katherine hears rural residents describe the DNR as an out-of-touch urban agency that imposes “ridiculous regulations” on people who actually live off the land. Some call it “Damn Near Russia.” Hunters and anglers complain that deer herd counts and season limits ignore what they see in the woods. Others describe “unworkable” rules on fish viruses and minnows. In Door County, people are furious that they need a $50 permit just to clean algae off their own beach. One mother says her son worries the DNR will inspect his freezer for illegal fish—evidence of what she calls a “police state.”

These stories give crucial context for understanding why a group like Hunter Nation matters. The people Katherine talks to already feel that wildlife and land-use rules are written by distant urban elites and enforced by regulators who “don’t get it.” Hunter Nation steps directly into that gap. By organizing hunters, landowners, and conservation-minded rural residents; by challenging state management decisions in court; and by pushing for gray wolf delisting as a matter of “sound science” and local control, Hunter Nation gives rural resentment a focused outlet. In many ways, it is filling the rural organizing void that the NRA once occupied but has increasingly ceded amid scandals, financial troubles, and declining membership. When they sue to force a wolf season or lobby for federal delisting, they are not introducing a new grievance—they are channeling exactly the frustrations Katherine documents with the DNR and its rules.

Katherine also shows that religion and family values are woven tightly into this worldview, but not in the caricatured way national pundits often describe. She attends groups that meet through churches and notes that, for many people, the congregation is a key source of identity and community. She recounts the backlash to Barack Obama’s 2008 line about people “clinging to guns or religion,” which landed as proof that national elites viewed their faith with condescension. In several conservative groups she hears a preference for church-based charity over government programs. Concerns about “family values” are tied to the decline of mom-and-pop farms and businesses, the “brain drain” of children leaving for cities, and the struggle for parents to keep a household afloat on rural wages.

That is exactly the terrain where Wisconsin Family Action operates. Katherine does not name WFA, but she describes a world in which religiously rooted voters want a way to engage politics that matches their moral language and their economic anxiety. WFA provides that bridge: traveling to churches across the state, resourcing pastors, framing legislative fights in terms of protecting families, and helping people “honor God with their vote.” In counties where party organizations are thin or distrusted, a group like WFA can do what Katherine’s rural residents say they want most—show up, explain what Madison is doing in plain language, and offer concrete steps to act.

Taken together, these patterns also clarify why certain candidates are well positioned heading into 2026. Katherine’s interviewees rarely talk about politics in terms of left/right ideology. They talk about who understands “people like us,” who respects rural work, who listens when there is a conflict over land, wildlife, or local schools. So when Congressman Tom Tiffany champions the Pet and Livestock Protection Act to delist the gray wolf nationwide and return management to states, he is stepping into a long-running story Katherine has already documented. Her groups may be arguing over deer tags, bear permits, and bass research rather than wolves, but the underlying question is the same: will decisions about rural land and wildlife be made by people who live there, or by distant agencies and courts? As Tiffany runs for governor, that message—coupling energy costs, regulation, and wildlife management to questions of local control—speaks directly to rural consciousness as Katherine describes it.

For those of us who work with campaigns and third-party organizations, The Politics of Resentment is valuable precisely because it refuses to flatten rural voters into poll crosstabs. Katherine reminds us that you cannot fix a sense of being ignored, shortchanged, and looked down on with one policy announcement or one ad buy. You have to decide which institutions will be present in these communities year-round—whether that’s a hunting organization, a family-policy group, a candidate willing to make the long drive, or all of the above.

The book is rooted in pre-Trump Wisconsin, and it doesn’t cover every dynamic of 2026: social media echo chambers, nationalized outrage cycles, and new issue clusters are largely outside its scope. But the core diagnosis has aged well. It explains why party labels can become liabilities even when individual policies are popular; why focused third-party groups like Hunter Nation and Wisconsin Family Action can punch far above their weight; and why candidates who align themselves with rural consciousness instead of fighting it are likely to outperform their party’s brand.

If you want to understand the political forces that will shape rural states in 2026—not just what voters say on a survey, but how they see themselves, their families, their churches, their land, and the people who regulate them—Katherine’s The Politics of Resentment remains one of the best starting points I can recommend.

John Connors

President, Campaign Now

111 Congress Avenue, Suite 400

Austin, TX 78701

References

Cramer, K. J. The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016.