The working class in pivot counties is older, less educated, economically stressed, and institutionally skeptical, making their profile, more than ideology, the key to electoral outcomes.

What to Know

- Pivot counties are dominated by voters without four year college degrees, particularly in manufacturing, logistics, energy, healthcare support, and skilled trades.

- These voters skew older, with outsized influence from Gen X and older millennials rather than Gen Z.

- Cultural identity and lived experience now outweigh party labels in shaping political behavior.

- Distrust of national media, political elites, and institutional leadership is a defining trait.

- Inflation, cost of living pressure, and job security consistently rank above social issues in voter priority.

The story of pivot counties is no longer about political volatility or momentary swings between parties. At Campaign Now, we define pivot counties as places where a specific voter profile has become structurally decisive over time. These counties did not simply drift away from Democrats in a single election.

Ballotpedia notes that they realigned around a working class identity shaped by sustained economic pressure, growing cultural distance from elite institutions, and a deepening belief that the political system does not respond to everyday needs. That alignment has now persisted across multiple cycles, turning what once looked like disruption into a durable political structure.

Why the New Working Class Voter Now Defines Pivot Counties

Understanding this voter is central to campaign strategy heading into 2026. The new working class voter is not disengaged, cynical, or detached from politics. These voters are attentive, opinionated, and closely focused on material conditions like wages, prices, public safety, and institutional competence. What separates them from earlier coalition models is how they process politics.

|

Working Class Voter Snapshot Economically pressured, outcome driven, and politically attentive. This voter tracks wages, prices, public safety, and basic government competence more closely than party labels or ideological framing. They follow politics, but they evaluate it through lived experience rather than media narratives. Culturally distant from elite institutions and professional class language, this voter is skeptical of symbolism and branding. Credibility is earned through clarity, consistency, and delivery. Trust, once broken, is difficult to rebuild. In pivot counties, this voter does not disengage. They decide |

Education and Age: Who the Pivot County Voter Is

Across pivot counties, educational attainment remains one of the strongest predictors of political behavior. Voters without a four year degree make up the backbone of the electorate. This does not mean they are disengaged from policy or incapable of complex analysis. It means their reference points are shaped by work, family, and community rather than professional networks or academic institutions.

Screenshot from PEW Research Center

Age is a decisive factor in how pivot counties vote, and Pew Research Center data helps explain why. Pivot counties are disproportionately shaped by Gen X and older millennial voters, cohorts that entered adulthood during repeated economic shocks.

Screenshot from PEW Research Center

Many came into the workforce as stable manufacturing jobs declined, lived through the 2008 financial crisis during prime earning years, and are now navigating sustained inflation that has eroded purchasing power. Their political memory is not abstract. It is built around wages that never caught up, institutions that promised stability but failed to deliver it, and bipartisan assurances that did not translate into durable improvement.

Industry and Economic Reality

The economic base of pivot counties is practical and exposed. Manufacturing, warehousing, energy production, agriculture, healthcare support roles, and transportation are common. These jobs are often physically demanding, schedule driven, and sensitive to economic downturns.

Reports from In Thes Times on working class attitudes show that voters in these roles consistently prioritize stability over growth narratives. They care less about stock market performance and more about predictable hours, affordable fuel, and manageable grocery bills. Inflation is not an abstract economic indicator. It is experienced daily at the gas pump, the checkout line, and the utility bill.

This helps explain why economic messaging that emphasizes long term transformation often fails to resonate. Voters are not opposed to change, but they are wary of transitions that ask them to absorb short term pain without clear personal benefit.

Cultural Traits and Identity

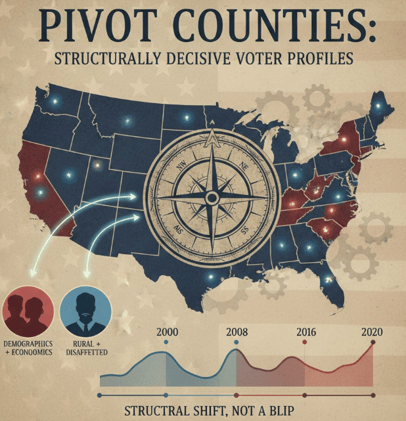

Research from the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group helps clarify why cultural identity plays such a powerful role in pivot counties. Partisan switching is rare, but when it happens, it reflects deep identity shifts rather than short-term issue disagreement. Among Obama to Trump voters, Democratic identification collapsed while Republican identification surged, signaling not just a vote change, but a re-sorting of political identity rooted in values, culture, and lived experience.

Culturally, pivot county voters place high value on self-reliance, local loyalty, and earned respect. Work is central to identity. Being useful, dependable, and productive carries moral weight. The analysis shows that Democrats lost the most ground among older, non-college white voters whose sense of belonging and recognition eroded as party language and priorities shifted. This was less about specific policies and more about feeling culturally misaligned with institutions and leaders perceived as distant from everyday realities.

That distance helps explain why certain messages land and others fail. Griffin’s findings show that voters who left the Democratic Party were more likely to hold conservative economic views and negative attitudes toward immigration, but also lower levels of economic anxiety, suggesting a values-driven rather than panic-driven shift. In pivot counties, messaging framed around dignity of work, fairness, and competence tends to resonate because it mirrors lived experience.

Distrust of Media and National Leaders

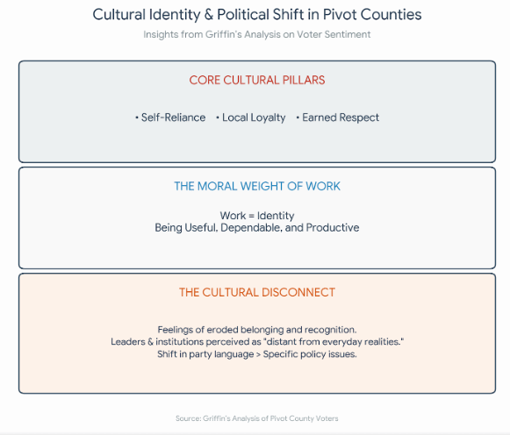

Distrust is one of the most durable traits shaping voter behavior in pivot counties, and it is grounded in long term trends rather than recent headlines. According to Pew Research Center, public trust in the federal government is near historic lows, with just 17%of Americans saying they trust the government in Washington to do what is right most of the time or just about always. That decline has unfolded over decades and cuts across party lines, reinforcing a broader sense that national institutions do not reliably deliver for ordinary people.

Screenshot from PEW Research Center

In pivot counties, this erosion of trust extends beyond government to national media and political leadership more broadly. Voters frequently view national outlets as biased, culturally distant, or disconnected from everyday realities. Political leaders are often seen as career oriented figures who speak fluently in professional language but produce little visible improvement in wages, prices, public safety, or basic competence.

Inflation and Economic Stress as the Central Lens

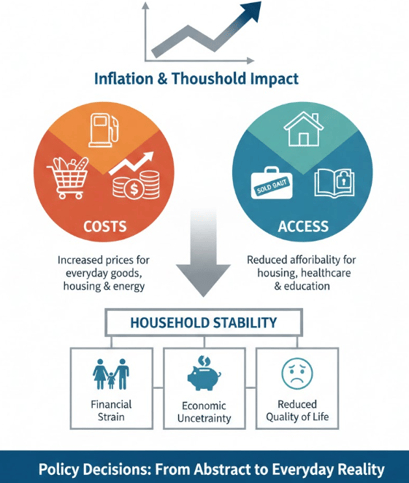

Economic pressure has become the primary way voters in pivot counties interpret politics, and recent analysis from the Brookings Institution helps explain why that lens has sharpened heading into 2026. Across issues ranging from health care and nutrition assistance to student loans, trade policy, and federal debt, Brookings scholars point to a common reality: policy decisions are increasingly felt at the household level, where costs, access, and stability matter more than abstract debates. Inflation has not simply raised prices.

It has forced voters to evaluate leadership through daily tradeoffs about rent, groceries, energy, health care, and debt. For working class voters, this pressure is cumulative rather than episodic. Wages have struggled to keep pace with higher costs, savings are harder to rebuild after repeated economic shocks, and debt feels riskier as interest rates and uncertainty rise.

When voters in pivot counties say the system feels broken or unresponsive, they are often describing this layered economic stress rather than a single policy failure. Inflation turns politics into a personal accounting exercise. Voters ask whether leaders understand how policy choices affect real budgets and real risk, not whether those choices fit a broader ideological framework.

Narrative Examples from Pivot Counties

Consider a warehouse worker in a Midwestern pivot county. He works rotating shifts that make family life unpredictable, pays noticeably more for fuel than he did just a few years ago, and has watched familiar local stores close or thin out. Headlines point to easing inflation or steady job growth, but those signals feel disconnected from what he sees around him. His paycheck stretches less far, his town feels smaller, and the promise that economic momentum will eventually reach him has been repeated often enough to lose credibility.

Or consider a healthcare support worker in a rural pivot county. She earns slightly too much to qualify for public assistance but nowhere near enough to absorb rising childcare, housing, and insurance costs without stress. Each unexpected expense carries risk. When she hears national leaders debate billion dollar investments, tax incentives, or long term economic transformation, the scale feels abstract. What matters more to her is whether the systems she relies on will remain affordable and functional next month, not whether they look impressive on paper.

These experiences explain why pivot counties continue to move in a consistent direction even as national messaging shifts. Voters are not reacting to party branding or campaign slogans. They are responding to whether candidates acknowledge these realities plainly and demonstrate an understanding of how policy decisions land at the household level. In pivot counties, credibility is built through recognition and specificity.

Wrap Up

Pivot counties reflect a broader shift that campaigns cannot afford to ignore in 2026. The working class voters who now anchor these places are not turning away from politics. They are judging it based on experience. Years of economic pressure, distance from national institutions, and repeated disappointments have shaped voters who are practical, attentive, and skeptical, but still open to candidates who earn their trust. Messaging that leans on ideology or symbolism tends to fall flat. Messaging that starts with empathy, plain language, and clear outcomes performs better.

For campaigns, the takeaway is direct. Pivot counties may not swing easily anymore, but they still matter. Winning here does not mean changing values or abandoning policy goals. It means explaining how those goals improve daily life in real terms. Heading into 2026, campaigns that speak plainly, respect voter skepticism, and show they understand local realities will be more competitive. Campaigns that assume trust will return on its own or rely on abstract framing risk locking themselves out of places that still decide close elections.