A wave of “foreign influence” and “baby FARA” laws at the state level is reshaping how campaigns, corporations and advocacy groups can spend and speak before the midterms.

What to Know

- Multiple states are tightening rules on political spending by foreign nationals and “foreign influenced” entities, sometimes going far beyond federal standards.

- New “baby FARA” statutes in Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Nebraska and Texas create state registration and disclosure regimes for work tied to foreign governments and adversaries.

- These laws often lack key exemptions found in federal FARA, pulling in corporations, nonprofits and trade associations that have never had to register before.

- Determining whether a company is “foreign influenced” can be complex and fluid, which raises real compliance risks for campaigns, vendors and media platforms.

- For 2026, these rules will affect how campaigns raise and spend money, how they vet partners, and how they talk about foreign policy and national security.

For years, “foreign interference” in American politics was mainly a federal story centered on the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), the Justice Department and high-profile violations. That is no longer true. Since early 2024 and accelerating in 2025, state legislatures and voters have begun building their own infrastructure to police foreign money and influence.

New ballot measures, campaign finance restrictions and “baby FARA” registration laws now sit on the books in key states, quietly changing the risk landscape for political spending and advocacy ahead of the 2026 midterms.

For campaigns, super PACs, advocacy groups and corporate government affairs teams, this shift is not theoretical. It touches everything from who can donate or fund ads, to whether a coalition partner has to register as an “agent” of a foreign adversary in a given state. It also raises a strategic question for both parties: how to weaponize foreign influence concerns without tripping over new legal tripwires.

What is FARA?

The Foreign Agents Registration Act is a federal transparency law adopted in 1938 that requires anyone conducting political or public-facing work on behalf of a foreign principal to register with the Department of Justice and disclose their activities.

|

FARA in a Nutshell FARA is a federal law that makes anyone acting in the United States on behalf of a foreign government or foreign entity publicly disclose their activities. It is a transparency rule, not a speech ban. States are now creating their own versions that reach far beyond the federal model. These new laws can apply to issue advocacy, digital communication, and even U.S. companies with foreign investors. Compliance is becoming a state-by-state challenge. |

It also contains broad exemptions for commercial activity, routine legal work, and organizations communicating on their own behalf. For decades, these carve outs meant most corporations and trade associations operated comfortably outside FARA’s compliance perimeter.

From “Foreign Nationals” to “Foreign Influenced” Companies

Federal law already bars foreign nationals, foreign governments and foreign corporations from making contributions or expenditures in federal, state or local elections. Many states simply mirror that rule. The new wave of laws expands the target. Legislators and ballot sponsors are increasingly focused on corporations with even small foreign ownership stakes and on entities they label “foreign government influenced.”

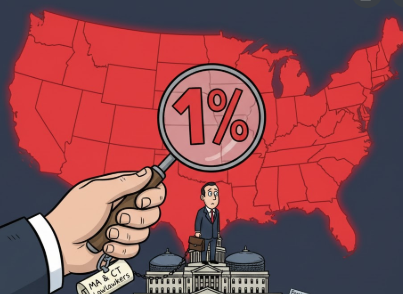

In Massachusetts, lawmakers have considered proposals that would limit corporate political spending when a single foreign investor holds as little as 1% of ownership, and similar ideas have surfaced in Connecticut. Maine voters passed a ballot initiative aimed at banning political spending by “foreign government influenced entities” that meet minimal thresholds of foreign ownership or control, before the First Circuit halted enforcement on First Amendment grounds.

These measures rely on detailed ownership tests that go well beyond traditional campaign finance screening. A publicly traded company or large privately held firm may have to trace its cap table, governance rights and any special shareholder agreements to determine whether it is covered. That analysis is not a one-time exercise. Ownership changes, new capital raises or corporate restructuring can move an entity in or out of a regulated category within a single cycle.

The practical effect is a new incentive for silence. Faced with ambiguous definitions and the risk of civil or criminal penalties, some companies and media platforms may choose to avoid state-level political or ballot measure campaigns altogether. Others will demand stronger representations and warranties from campaigns and allied groups before carrying their ads or accepting their checks.

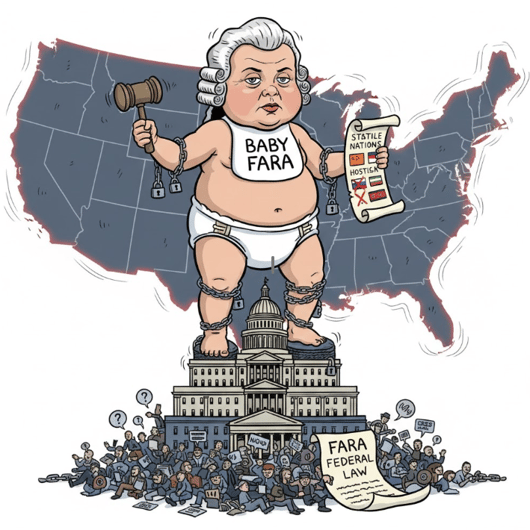

Baby FARA: State Registration Rules Arrive

A second front is opening through state-level foreign agent laws. Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Nebraska and Texas have enacted statutes modeled loosely on the federal Foreign Agents Registration Act. These “baby FARA” laws require individuals, firms and organizations to register with state authorities if they engage in certain activities on behalf of, or with support from, foreign governments or designated “foreign adversaries.”

In Arkansas, representatives of “hostile foreign principals” such as China, Russia, Iran or North Korea must register if they try to influence state policy or elections for state or local officials. Louisiana and Texas now require lobbyists who advocate for foreign adversaries or their affiliated entities to register and disclose the nature of their relationship and their lobbying agenda.

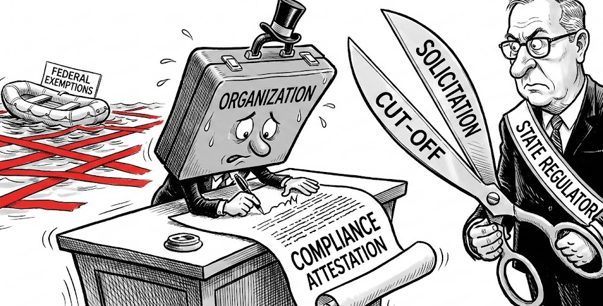

Nebraska’s law reaches a broad range of public affairs and fundraising work connected to adversary nations and tracks the federal definition of covered activities while omitting many of the federal exemptions. Florida takes a different route by using its charitable solicitation law. Nonprofits and fundraising professionals are barred from soliciting or accepting contributions from “foreign sources of concern,” including entities tied to certain adversary regimes.

Organizations must attest to compliance in order to keep raising money in the state and can be cut off from solicitation if they violate the rules. Critically, these state laws do not always copy the exemptions that make federal FARA manageable for many commercial actors.

Activities that would be exempt at the federal level, such as work that is purely commercial or already covered by lobbying registration, may still trigger state reporting and public disclosure. That gap is what makes the new laws so consequential for global companies, diaspora nonprofits and issue groups that operate in multiple states.

Compliance Risk for Campaigns, Donors and Platforms

For campaigns and party committees, the new rules are not just a legal headache. They are a political vulnerability. Opponents will look for any failure to vet donors, vendors or coalition partners properly. A candidate who accepts support from an entity that should have registered as a foreign agent under state law, or from a corporation later tagged as “foreign influenced,”, according to Maine, for instance, can be hit with a narrative about foreign money and shadow influence even before regulators act.

At the same time, advocacy coalitions that span multiple states will need to build a higher level of compliance discipline into their work. A group that is exempt from federal FARA and fully compliant with a home state's campaign finance law may still trigger registration in Texas or Nebraska simply by lobbying or running ballot measure campaigns while receiving support from an entity based in a listed country.

Trade associations and national nonprofits that speak on energy policy, technology, higher education or human rights often have members or donors with foreign ties, which makes this a live question rather than a remote possibility.

Media and technology platforms are a quiet but critical part of this story. Many of the new laws presume that online ads, digital fundraising campaigns and sponsored content can be traced back to their source. If state regulators start to probe whether platforms carried ads paid for by foreign influenced entities, the easiest response for risk-averse firms may be to tighten their own internal screens and decline more political content in high-risk states. That will change the advertising mix and could make it harder for down-ballot campaigns to reach voters cost-effectively.

Wrap Up

Heading into the 2026 midterms, foreign influence laws will sit alongside voter ID, redistricting and mail ballot rules as a key structural factor in campaign planning. Both parties will try to turn the issue to their advantage. Republicans are likely to stress national security and competition with China and Russia. Democrats will emphasize transparency and corporate accountability. Each side will highlight the other’s donors, partners and surrogates with foreign ties.

For strategists, the operational questions are immediate. Finance teams need new screening tools for donors and corporate partners in states with tighter foreign influence rules. General counsel offices and compliance vendors must map where baby FARA registration might be triggered and advise campaigns and aligned organizations on whether to register, restructure relationships, or avoid certain activities. Creative teams will need to understand how far they can push foreign influence messaging without undermining their own coalition.